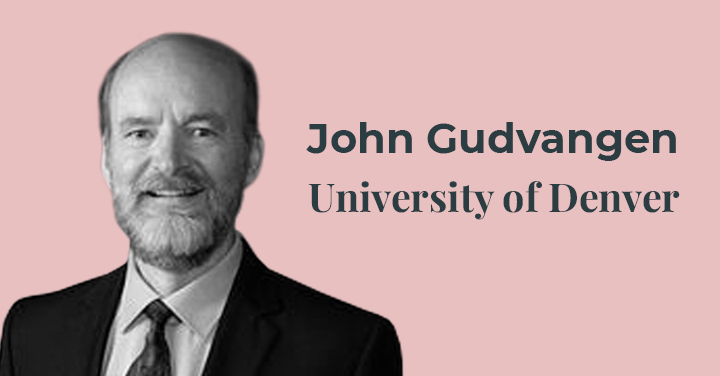

Phillip Levine

Professor of Economics

Wellesley College

I hate going to cocktail parties. As an academic economist, the fact that I’m an introvert probably doesn’t come as much of a surprise. I am the type of introvert, though, who can put on a good public face (although it is exhausting!), so that isn’t really the problem.

Where things typically head south is when I meet someone new. I tell them what I do and that typically leads to one of two questions: is the stock market going to go up or are interest rates going to come down? The intentions of these questions are largely the same. When I indicate that finance is not the focus of my work, I can see their eyes look past me to see if there are more interesting people they can talk to. There probably are.

At some point, though, I became popular. It occurred around the time the children of those in my social circle approached college age. Although I cannot give investment advice, my expertise in higher education finance, and particularly college pricing, is a pretty good alternative. They all want to talk about that.

The conversation usually leads to a common list of questions that these parents want the answer to. My goal here is to present a top ten list of those questions (in the David Letterman spirit for those old enough to get the reference). That way, if you see me at a cocktail party, we can talk about the Red Sox, which really is what I would prefer to talk about!

1) Why does college cost so much?

This one definitely tops the list. Media stories about skyrocketing costs and colleges charging $90,000 per year are easy to find. But only a small fraction of college students is asked to pay that much. Most students pay less because of the availability of financial aid. If you have high levels of income and assets and if your child attends an elite private college, you may find yourself facing costs that high. Everyone else pays less, and often much less, because of the prevalence of financial aid.

2) How would I know how much I will have to pay?

That is the obvious follow-up question. The financial aid system is notoriously complicated. Most families have relatively simple finances, but for some, only a CPA can understand them. Parents who are self-employed or small business owners are high on that list. The financial aid system needs to set a price for all families, not just the vast majority with standard finances, so it seeks to determine a comprehensive assessment of income and assets. It is the exceptions that cause the problem and make life difficult for everyone else.

A little over a decade ago, though, the federal government required colleges and universities to introduce “net price calculators,” which are supposed to make it easier for parents to get an estimate of what they will have to pay to attend a particular school. That was the idea. Easier may be a euphemism in this case. Still, they are an available tool that sometimes can be helpful.

For the purposes of shameless self-promotion, I started a non-profit organization that provides a very simple way for families to get a quick, ballpark estimate of how much it would cost for their children to attend participating institutions. Several dozen schools currently use it, and you should check it out at myintuition.org. I think it’s great!

3) Is a college education worth it?

This is a question that is motivated by recent public opinion polls indicating more and more people are skeptical about the value of a college degree. In my view, those concerns largely represent issues related to its cost, which I’ve addressed earlier. The concept of “worth” is also about the return students receive if they pay that cost. We know a lot about that. To be blunt, for the typical college student graduating from a four-year college, the earnings gain associated with that degree is as high as it has ever been.

Are there students who do not benefit much? Absolutely. A student’s choice of major plays a large role in that process. It must at least partly be related to interests and abilities, not just earnings. Engineers and computer science majors make more than others after graduation, but happiness counts too. Research also shows that the type of institution students attend matters. For instance, graduates of for-profit institutions do not benefit as much from their investment.

Yes, many colleges build fancy new student centers and dormitories and offer exciting amenities. If you can believe it, some view these expenditures as excessive. Do those facilities improve the educational instruction their students receive? No.

That does not mean, though, that they are wasteful. What they intend to accomplish is to attract more students. More specifically, they attract more students who pay higher prices. Public institutions in particular are likely to engage in these practices as a way of attracting out-of-state residents who pay much more to enroll than state residents.

The actual cost of educating students is not cheap. A college’s main sources of costs are instruction, academic support, and student services. And these days, there is also a high demand for career and health services, including mental health. Funds to cover those costs have to come from somewhere. Providing “unnecessary” perks to increase revenue to help cover those costs may be a good investment for the institution.

5) Why does it cost so much to educate students?

The average cost of educating a student at a typical four-year residential college or university may be a number like $40,000 or $50,000. That seems like a lot to pay for a professor and a chalkboard with dozens (hundreds?) of students in the class.

But think about it this way. It would not be uncommon for a reasonably well-financed K-12 school system to pay $15,000 to $20,000 to educate a student. The most obvious difference between primary and secondary schools relative to residential colleges is that the latter house and feed their students. I don’t think $15,000 per year to accomplish that goal seems unreasonable. Then think about the nature of the staff and facilities. A college-level science building has a lot more than a Bunsen burner. The teachers spent perhaps a dozen years in college and beyond to become qualified for their positions. They cost more than high school teachers. When you add it all up, it isn’t crazy.

I should also note that the elite colleges and universities that charge the $90,000 only to their students from high income families often spend considerably more than that, on average, to educate their students. It may be well over $100,000. Their large endowments cover the difference. Whether top notch facilities and a Nobel prize-winning faculty provide that much additional value is unclear, but the market suggests families want that.

6) What is merit aid, and should I anticipate that my child would receive it?

The term financial aid sounds like it is funding that helps people pay for college based on their financial need. It turns out, though, that colleges and universities also offer another form of financial assistance that is often referenced as merit aid. In theory, merit aid reduces the cost of attending college for its recipients based on academic performance. If an institution views your grades, test scores, or other aspects of a student’s record as meritorious, they may lower the cost for that student. That seems to make sense.

But not everything that seems to make sense is as straightforward as it sounds (shocking, isn’t it?). And there are reasons why this concept of merit aid is a bit misleading. First, merit aid and need-based often offset each other. If a student with “financial need” is awarded merit aid, it may reduce their need-based financial aid award, at least to some extent, because the merit aid reduces their need.

For higher-income students who are not eligible for need-based financial aid, merit aid always reduces the price below what is established by the full cost of attendance, or sticker price. But at many institutions, large numbers of higher-income students receive these awards. It is more a form of marketing than merit. Psychology is a powerful force, and colleges use it to attract students.

7) Is it better to save or borrow to pay for my child’s college education?

Now we’re moving back towards investment advice, which is dangerous territory for me. All appropriate disclaimers should be assumed!

That said, waiting until your child is 18 years old to figure out how you are going to pay for college is a mistake. The minute your child is born, if you anticipate your child is bound for college (and obviously there is some uncertainty there), that cost is looming. You have the rest of your life to pay for it. You can pre-pay through saving, or you can pay ex-post by borrowing, but it’s the same cost either way.

Smoothing that cost over your life is probably preferable. There is nothing wrong with using debt to cover some of the cost, but saving probably makes sense as well. If you are going to save, doing so in a tax-advantaged manner certainly is a wise choice.

That is where 529 plans come into play. Whether you do so through state-sponsored savings plans, or pre-paid like Private College 529 Plan, it is a personal choice. Both offer advantages. In general, though, diversification is always a wise investment strategy, and this one is no different.

8) Will saving for college affect my child’s eligibility for financial aid?

The simple answer is yes it will. Any assets you have are incorporated into the formula used to determine financial aid. Greater assets mean less financial aid. College savings represent an asset. But the “tax” on savings in terms of reduced financial aid is not large. One could argue that rearranging your preferred method of paying for college based on a relatively small cost represents the tail wagging the dog. I do not advise that strategy.

9) Should I apply early decision if I want financial aid?

One problem with our higher education system is that students do not find out the actual price they will be asked to pay at an institution until after they are accepted. That’s just odd. But it also complicates college decision-making. For students who apply to several institutions, they at least can compare prices if they are admitted to more than one.

But students who apply early decision do not have that luxury because many schools’ early decision applications are binding. If you apply, you commit to enroll if you are accepted. There goes the prospect of comparing prices.

It turns out, though, that there is an out. Students requesting financial aid can back out of their commitment if they do not view their financial aid award as sufficient. That isn’t as good as being able to compare offers across schools, but it does help. If the student really wants to attend a certain college and the financial aid award makes that college affordable for them, maybe it’s OK that they may have gotten a somewhat better deal elsewhere.

10) Will we ever figure out how to make college broadly affordable?

And that’s the $64,000 question (again, for those old enough to get the reference!). For more shameless self-promotion, I wrote a book published in 2022 on college pricing. It makes for great bedtime reading!

An important conclusion from my analysis is that college is less expensive than people think, but it still could be more affordable, particularly for lower- and middle-income families. I think a reasonable goal of the higher education system is to create a pricing structure so that every student can attend an institution that is the best fit for them regardless of their ability to pay. We do not have that now.

Identifying problems, though, is much easier than solving them. Ultimately, the solution requires greater societal resources being devoted to the higher education system to attain sustainable, affordable pricing. I do not pretend to have easy solutions to achieving that goal, but without doing so we will be left with a system that limits economic opportunity and social mobility, both of which I believe are universal social goals.

And stating that message really is the reason I don’t do well at cocktail parties!